Go behind the scenes of Alberto Salas Plays Paka Paka con la Papa written by Sara Andrea Fajardo and illustrated by Juana Martinez-Neal, available in both English and Spanish Language editions.

Read on for an interview with Sara, Juana, and Connie Hsu, VP, Executive Editorial Director at Roaring Brook Press to hear how this book was made, preview interior art, and learn more about the real Alberto Salas!

Connie: Hello, Sara and Juana! I’m excited for us to chat about Alberto Salas Plays Paka Paka con la Papa. I always love a good origin story, and this manuscript definitely has one. Truth be told, I didn’t immediately connect with the original submission. But fortunately, Juana, you had a chance to take a peek at Sara’s manuscript because you’re both represented by the same agency. Juana, can you share the spark you saw in the story and what you said to me when we first talked about it?

Juana: Hi everyone! Thanks for this! Stefanie had told me that Sara was working on this manuscript because it was about someone from Peru. At the time, I didn’t know about Alberto. I was curious and wondered if I could read the manuscript. I did but got distracted until I read the Author’s Note. This paragraph below to be more precise.

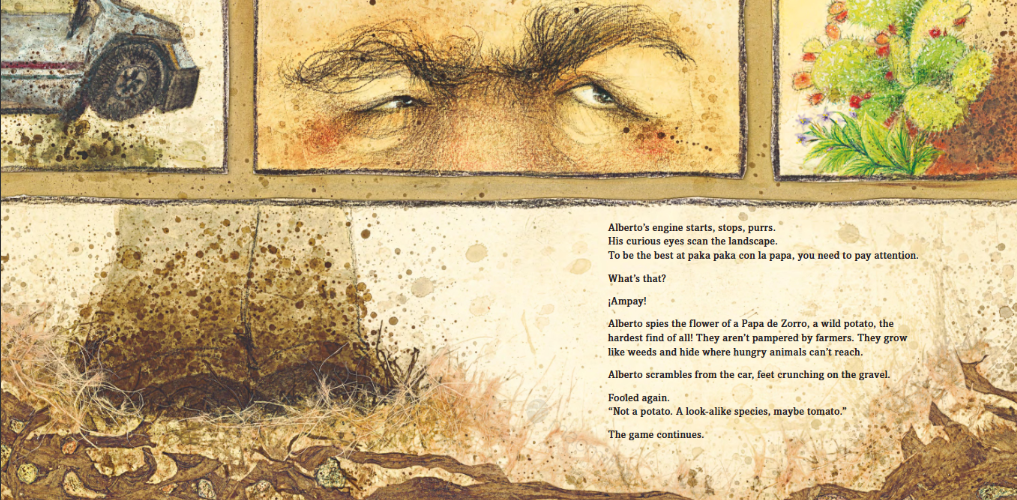

“The car traveled slowly. Our eyes were on the landscape, searching for those tell-tale stars. We scanned the top of cliffs and beneath cacti plants, places where the potato wild relatives—his favorite tubers—like to grow out of the reach of animals. Every now and again, Alberto would call out, “There!” And the car would pull to the side of the road. We’d pour out of the car to take a closer look. Often Alberto would shake his head, no, just a look-alike species, maybe a tomato. But, just as often I’d hear him squeal in delight, “Es tan bonita” (It’s so beautiful) as he’d marvel at the delicate potato flowers like a little boy about to pick a bouquet.“

As I read, “es tan bonita” I was moved and sold. I shared that with you, Connie. The book is in the author’s note, Connie, I told you on the phone. And it was because it was intimate, personal and with so much care and love in those words. It felt as if there Sara allowed herself to just write like she wanted instead of how she thought she should write this story.

Connie: Juana, thank you for looking so deeply at the author’s note and feeling Sara’s deep connection to Alberto through her words there. Sara, you were so open and gracious about hearing these notes and about working on the story prior to acquisition. It’s so wonderful and rewarding to work with an author who is game for collaboration. Can you share your response to our editorial call and how it shifted your approach to telling Alberto’s story? And also tell us a bit more about how you got to know Alberto and where your initial spark for sharing his story came about?

Sara: I did love the original version and still do, it remains the beating heart of the book we have today. But as a writer I’m always willing to try new things, see how a different approach might shape a story in surprising ways. What resonated with me most about our conversation was the suggestion that I put a lot of the scientific content into the back matter to free myself to tell what it felt like to be on a journey with Alberto. From the beginning I wanted to make this a book about the value of play and the gifts of an Andean childhood. Early on in the writing process, however, I got a critique from a writer I really admired who commented on the fact that they thought no kid would relate to playing with potatoes. The comment was in no way ill intentioned, it was meant to be helpful, but it still made me doubt my original idea of rooting Alberto’s story in play. It made me wonder would kids in the U.S. relate to a boy from the Andes playing with potatoes. I kept going back to the idea of yes, I mean, how many people grew up with Mr. Potato Head? Still, that feedback shifted my direction to a more traditional format. What the call did for me was give me the space to simply block everyone out, trust my instincts, and honor my original vision for the story.

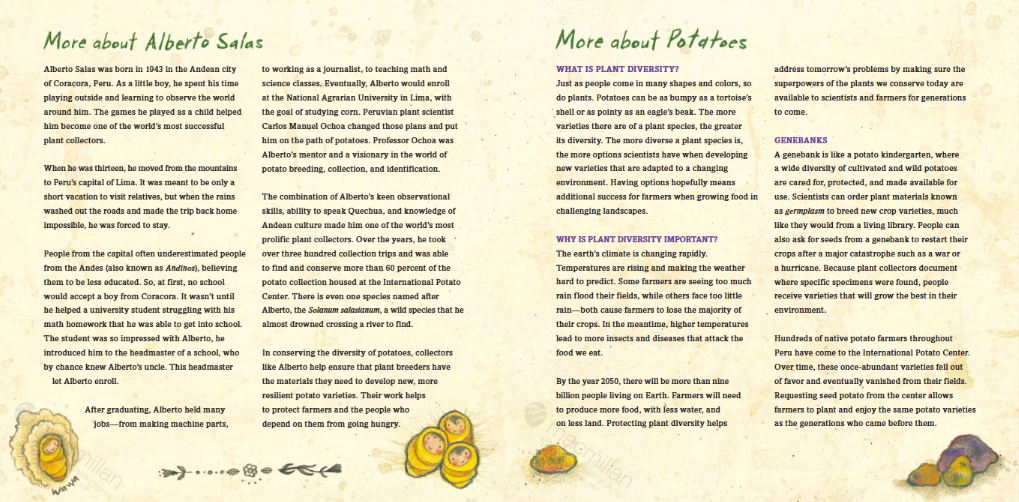

I first met Alberto Salas while working as a communications consultant for the International Potato Center. He’d just returned from a collection trip, and the head of the genebank at the time, Dr. David Ellis, said I really needed to meet him and hear his stories. One hour with Alberto and I was sold. He tells tales of the road with a sparkle in his eye that makes looking for potatoes seem like the greatest adventure in the world.

What I loved about Alberto is that he consistently emphasized that speaking Quechua and growing up in the Andes were integral to his success as a collector. And when I asked how he became such a prolific potato protector, he gave the most simple response, “because I never stopped playing.” As the daughter of a retired Quechua professor who also grew up in the same region of the Andes as Alberto, I really wanted to honor that part of my heritage and Alberto embodied everything that I love about the Andes. I simply had to write his story.

Connie: Sara, thank you for the background on your creative process and how meeting Alberto inspired your book. I’m so glad you followed your creative instincts. It’s clear from the warmth and care in your story how much of this came directly from your heart. During the editing process, you had many fun stories to share about Alberto, and it’s too bad we couldn’t make the back matter many pages longer to fit them all. Do you have a story about your time with Alberto or a fun fact about the work at the International Potato Center that you wished we could’ve included in the book?

Sara: There are so many stories about Alberto that I wish I could share that it would take tomes not a picture book to cover them all. One of my favorites, however, is when he was in Bolivia and his car got stopped in a very remote area by suspicious villagers. Alberto was the only one in his group who spoke Quechua and was listening to their conversation. He knew they were in grave danger, because recently several of the village’s livestock had been stolen and here they were, strangers, surely the culprits. As time passed Alberto needed to relieve himself so he asked for permission in Quechua. The villagers were shocked to hear him speak their language, and immediately changed from being hostile to embracing the group with warmth. They asked Alberto why he didn’t tell them sooner that he was one of them? It’s just so emblematic of how knowing a culture and language can open doors and turn you from suspect to friend.

A fun fact about the International Potato Center, is just how long plant breeders work to develop new varieties. It can take up to 18 years to produce a potato variety with desired traits such as high in iron or disease resistance that is also tasty enough for people to want to eat. I can’t imagine working for that long, with one goal, failing again and again, yet remaining committed to the vision of delivering crops that can feed a hungry world.

Connie: Sara, your anecdote speaks to Alberto’s ability to connect with people far and wide, and it’s incredible work that the International Potato Center conducts. I’m so glad you were able to highlight their efforts in the back matter of the book. Juana, you also had a chance to meet Alberto. Can you tell us more about that? I recall from our conversations that the feeling of getting to know Alberto hit really close to home for you.

Juana: Yes, Alberto reminded me a lot of my dad who had passed a couple of years before I met with Alberto. Sara was also there. We met on the patio of a restaurant (I think he or someone in his family owns the place – Sara may remember this). I felt it would be best to meet him in person since I was working on a book about him. I remember the moment clearly. Alberto sat at a table in front of me. I listened to him tell us stories about his work and watch him closely. I was observing him and trying to memorize him and how he moved and acted for when I had to sketch him for the book. The more I watched him, the more I felt he felt like my dad. The way he occupied the space, his presence, the way his head and neck moved slowly, his accent, his size, his posture. It was unsettling and moving at the same time. I never told him.

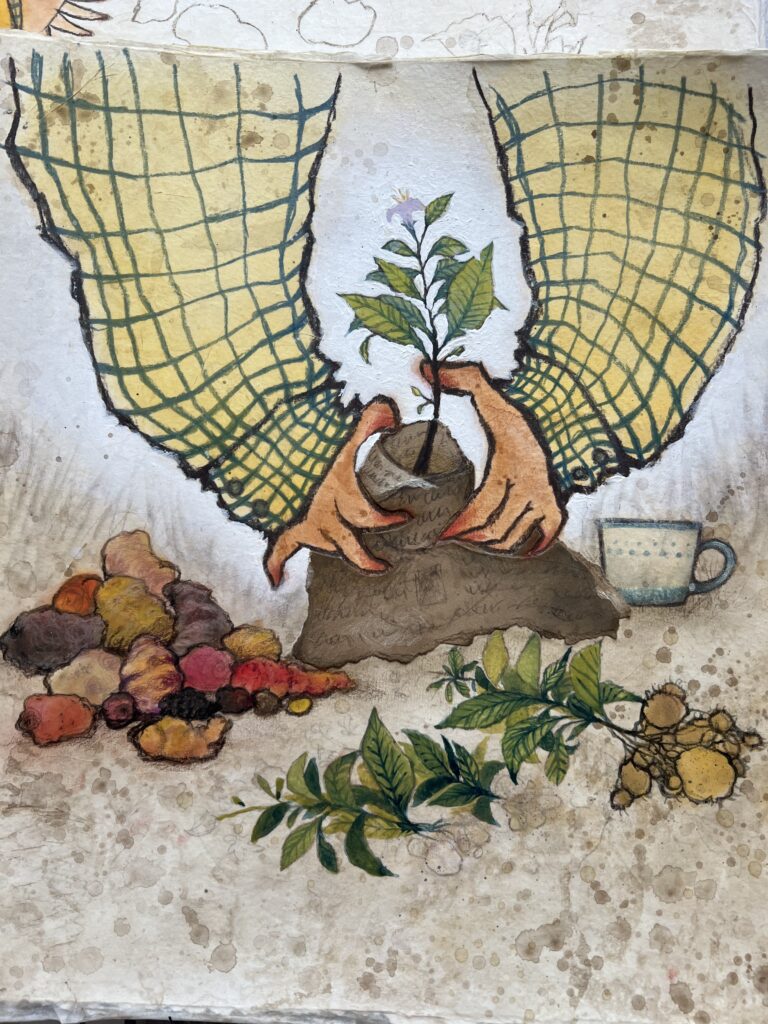

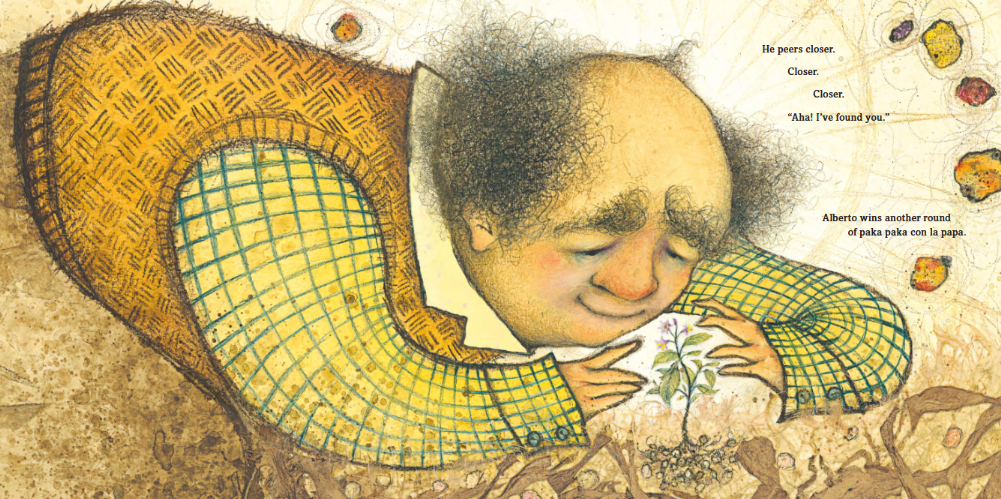

Connie: Juana, what a moving memory of meeting Alberto and seeing the similarities to your dad. I can see that connection you had with Alberto conveyed through your art. His body language as he’s bent down, looking at a potato flower. His excited run towards a possible find. The gentle way he cups the potato plant as he lifts it from the dirt. Please share more about your art process, from how you first approach illustrating Alberto to what your ultimate vision for the art became.

Juana: Alberto was hardly changed from my early sketches. I knew who I was illustrating mainly because I was mixing the person I met at the patio in a restaurant in Lima and my dad. I thought I knew how Alberto moved and how he acted because I had observed my dad all my life.

One thing that was clear while working on the sketches was that I wanted to replicate the texture of a potato and the soil it is in. I wanted the paintings to feel gritty and mimic, in some way, the feeling we get when we put our fingers in the soil. I imagined Alberto did this in his potato hunting adventures and explorations. But how could I convey that feeling with materials? That was the puzzle I had to solve so I embarked myself in my own hunt to find the perfect materials for the book — and it took a while.

Where I am now, I’m at least an hour away from the closest art store so I looked online for what felt right and ordered papers. But it was until a few months later when I was in Phoenix for an event that I got a chance to visit an art store in person. There, I went through papers looking, touching, flipping, sorting, pulling, getting them back in their place. Until, I pulled one and I knew immediately it was the one! I gasped as I pulled the paper closer to my face, “It’s you! I’ve been looking for you for so long!” And led me to understanding that for this book I had to add collage to my technique.

The rest of the materials were my conventional mixed media materials: colored pencils, pastels, acrylics, gesso, and one other paper that I collaged in the work. This other paper was pink and fuzzy, almost hairy. It was perfect to convey the sense of grass growing wild in the fields of Peru, and at the same time completely opposite to the rough, gritty, textural, dark paper I didn’t know I had been looking for a while.

As the manuscript itself felt like an adventure, I included panels in a couple of spreads. I thought it broke the pacing of the spreads and made it more fun and interesting — just like Alberto.

Connie: Juana, your journey with your art style sounds much like Alberto’s potato hide-and-seek! I remember visiting you in your studio around the time you made your discovery with collage. It was thrilling watching your creative energies at work.

Sara, it’s such a leap of faith for an author to put their story into the hands of an artist. I’m sure you were eager and excited to see Juana’s illustrations come to life. How did it feel to get your first peek of Juana’s art and her depiction of Alberto? What are some of your favorite spreads from the book? Were there any pleasant surprises or fun details?

Sara: Even when this story was still a seed, I knew in my heart that Juana was the person to illustrate this story. Her ability to capture the essence of a person with warmth and depth is such a hallmark of her beautiful work, so I knew this book was in the very best hands. I’m also in the unique position as a writer in that I’ve worked in visual communication for over 20 years, many of which focused specifically on agriculture. So, when I first saw the initial sketches, I was looking at them through two lenses, as an ardent admirer of Juana’s art and with a critical eye, in terms of how I might best support the team with the information and materials that could help bring out the botanical, geographic, cultural, and scientific accuracy at every level of how we told this story. I was so grateful for how receptive everyone was to getting things right.

What I found particularly poetic about receiving the first sketches, was that I happened to be in Arequipa, Peru when they landed in my inbox. I knew Juana’s family was from this region of Peru, and it just felt so fitting that it would be in her ancestral home where I would get my first peek of what would one day become Paka Paka. While every spread is exquisite, the one that left me breathless and continues to be my favorite is one towards the end, where Alberto has finally found his papa de zorro. I don’t know how Juana did it, but that is 100 percent Alberto on the page. From the loving gaze in his eyes, to how he cups his potato treasure, to the gentle protective curve to his body. It was almost as if Juana had been there herself.

As for surprises, I’d say the biggest surprise is when I showed the book to Alberto and his daughter Elisa. They were so tickled over how Juana knew to illustrate Alberto in his little yellow jacket. It sent a chill up my spine when they shared that he always went to the field in that jacket. Juana didn’t know this, yet she somehow channeled it on to the page. How magical is that!

Connie: Sara, those are both such beautiful memories, as you recall seeing Juana’s sketches and also Alberto and Elisa’s faces as they saw the book for the first time. These first experiences can last a lifetime! Also, how wonderful that your dream artist, Juana, connected with your story and gave Alberto and his quest so much life through her art.

To wrap up our Q&A, I’d like to ask both of you, what do you hope readers leave with after reading Alberto Salas Plays Paka Paka con la Papa and/or Alberto Salas juega a la paka paka con la papa (Spanish edition)?

Sara: I hope that readers will look at our world, plants and potatoes through new eyes. There is so much to discover if we simply know how to look.

Juana: Oh, this is an easy question. I hope readers take the time to observe nature. This is what got Alberto started and look how well it paid off!

Connie: Beautifully said! Hopefully readers will want to embark on their own quests to find their true calling, just like Alberto!

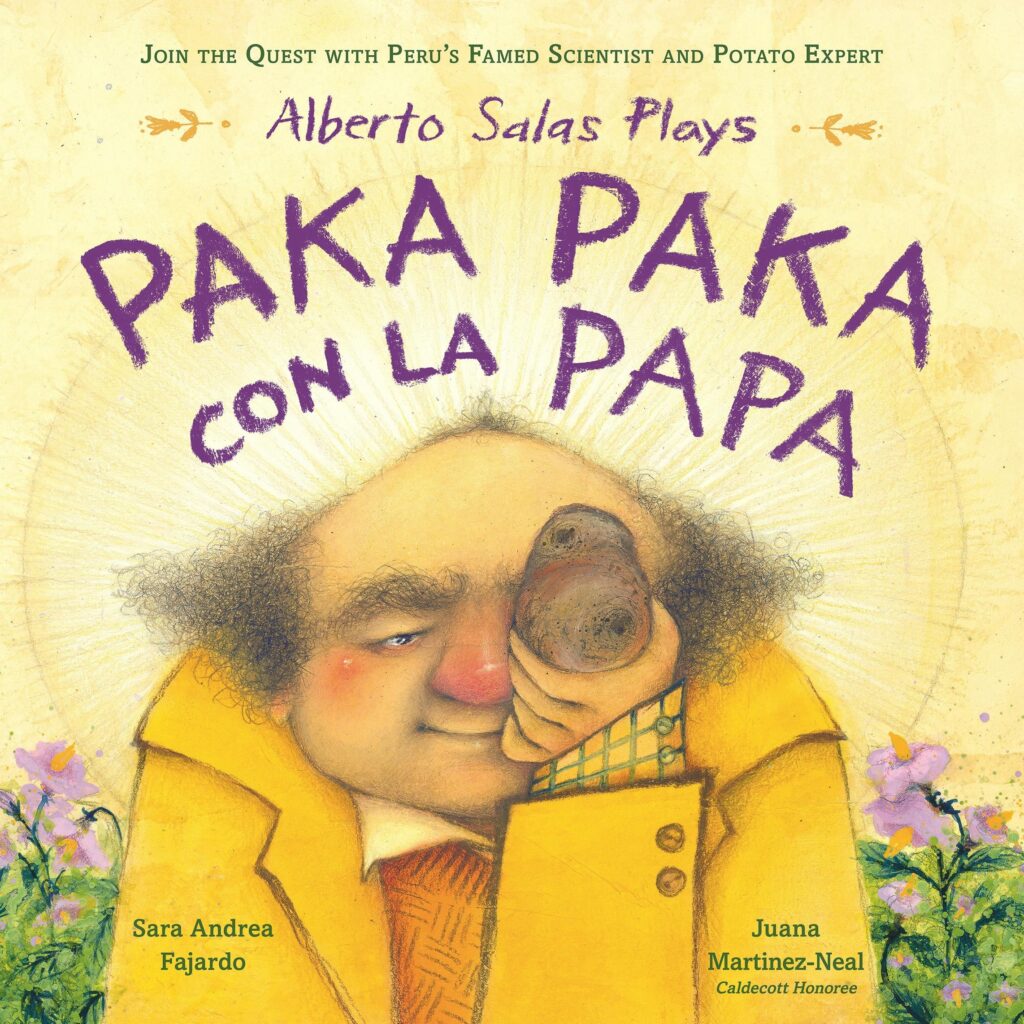

About Alberto Salas Plays Paka Paka con la Papa

Alberto Salas Plays Paka Paka con la Papa

*Also available in Spanish!*

By Sara Andrea Fajardo; illustrated by Juana Martinez-Neal

Ages 4-8

On Sale Now!

What can a potato do? To Peruvian scientist Alberto Salas, they have the power to change the world. Go on the hunt with Alberto for for wild potatoes before they go extinct in this playful picture book biography, gorgeously illustrated by Caldecott-honoree Juana Martinez-Neal.

High up in the Andes mountains of Peru, agricultural scientist Alberto Salas is on a quest. A quest… for potatoes.

Up and down the Andes mountains he goes, playing an epic game of paka paka con la papa, potato hide and seek. These potatoes are special: they have the power to feed the world.

Alberto doesn’t have a second to waste. The climate is changing and Alberto must find each and every one to save them before they go extinct.

The game is on!

Alberto races and peers and prods. Drives and trods and climbs. Will he find the potato he seeks? Will he win the game of paka paka con la papa?

Author Sara Andrea Fajardo’s spirited biography about “the godfather of potatoes” is paired with lush art by Caldecott-honoree Juana Martinez-Neal to capture how celebrated scientist Alberto Salas brings joy, curiosity, and fun to his very important, life-changing work.

Praise for Alberto Salas Plays Paka Paka con la Papa

★”Thematic connections to environmentalism and sustainability in our changing modern world, told through a Latinx lens, this is a highly recommended title for all nonfiction collections.” –School Library Journal, starred review

★”A lovely tribute to an unassuming yet impactful changemaker.” –Booklist, starred review

★”In a warm palette, Caldecott Honoree Martinez-Neal’s lush mixed-media illustrations convey Salas’s dedication and the potatoes as jewels hiding in an ever-shifting landscape. Fajardo smartly melds playful language with an urgent conservationist message…” –Publishers Weekly, starred review

★”[A]n affable, often playful tone and a loose yet incredibly informative narrative peppered with words in Spanish and Quechua, Fajardo recounts the potato expert’s adventures in all their glory…” –Kirkus, starred review

★”This tribute to a contemporary figure will no doubt strike a chord with young readers.” –BookPage, starred review

“Fajardo’s playful narrative brings readers along on Salas’s quest, touching lightly but directly on other serious issues that affect his work, such as climate change and human encroachment on natural habitats.” –Horn Book